Meet Norman Rockwell, American Illustrator

Overview:

This lesson will introduce students to Norman Rockwell, a professional artist

and renowned American illustrator. Images from books, the internet, written articles and class discussion will be used to explore his work. Students will describe, reflect and assess the images identifying the intentions of Norman Rockwell regarding the imagery in relation to historical events in the American culture.

This lesson is designed for one 60-minute class period.

Enduring Understandings/ Essential Questions:

- Norman Rockwell was a famous American illustrator.

- Illustrators are storytellers. They create pictures that tell the story.

- His paintings show what life was like in America from the early 1900’s to the 1970’s.

- Norman Rockwell painted works that made people think about their lives. We can learn about Norman Rockwell by reading books, visiting museums that have his works, studying his paintings and visiting the digital collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

- Norman Rockwell was inspired by his surroundings (nature, politics but also ordinary events of his friends and neighbors.)

- Who is Norman Rockwell?

- What is an illustrator?

- What do you know about Norman Rockwell?

- How might you learn more about Norman Rockwell?

- What things influenced Norman Rockwell’s work?

- What do you think the Four Freedoms communicated to the American people?

- Grade

- 9-12

- Theme

- Four Freedoms

- Length

- This lesson is designed for one 60-minute class period.

- Discipline

- National Core Art Standards; Language Arts: Reading

- Vocabulary

- Cultural metaphors; Editor; Freelance; Illustrator; Patriotic; Representational Art; Series; Sketch; Symbol

Objectives:

- Students will share any prior knowledge regarding Norman Rockwell that they may have.

- Students will use computer technology to search for information about Rockwell, beginning with The Norman Rockwell Museum Digital Collection: collections.nrm.org

- Students will observe images and state what they see.

- Using prior knowledge, the information from the articles and internet resources, the students will make describe meanings of artworks by analyzing how specific works are created and how they relate to historical and cultural

- Students will make personal judgments on Rockwell’s work.

- Students will listen attentively to one another as they share personal responses about the specific artworks.

- Students will discuss and assess the information presented in a biography article.

Background:

Norman Rockwell (1894–1978)

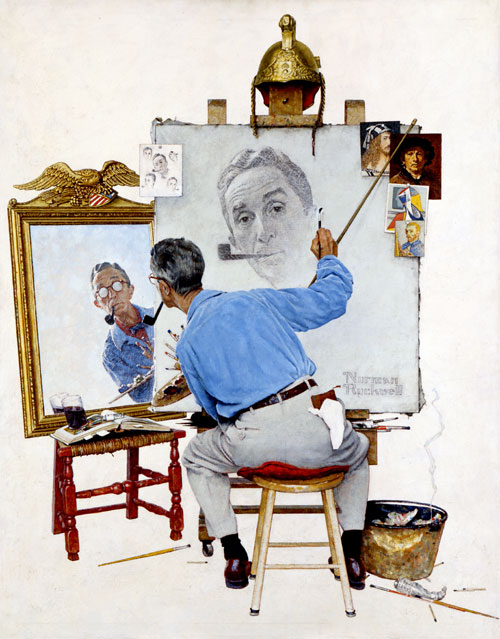

Triple Self-Portrait, 1959

Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, February 13, 1960

Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 34.75 inches

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRACT.1973.19

Humor and humility were essential aspects of Norman Rockwell’s character, so when asked to do a self-portrait that would announce the first of eight excerpts of his autobiography, the result was lighthearted and somewhat self-deprecating. The painting provides the essential elements not of his life as an illustrator, but of the specific commission. Rockwell’s life is far too eventful and complex to begin to approach summation in a single work, so he limits the composition to himself, his artists’ materials, his references, a canvas on an easel, and a mirror.

There are more inconsistencies in this painting that are cause for wonder. Rockwell was a stickler for neatness, but here he has scattered matchsticks, paint tubes, and brushes over the studio floor. The glass of Coca-Cola, Rockwell’s usual afternoon pick-me-up, looks as if it will tip over at any moment. Other discrepancies can be explained away. He has traded his usual Windsor chair for a stool (easier to see more of him?) and his milk glass palette table for a hand-held wooden palette (an economy of picture space?). In real life, Rockwell’s mirror was not topped with an eagle holding arrows, cannon balls, and a shield. The eagle, taken from the outside of Rockwell’s studio for use as a prop, may have been added to send a message. Most of the features ring true: He did tack or tape studies to his drawings or canvases and he did immerse himself in favorite artwork before beginning a project. That Rockwell’s eyes cannot be seen bothers some who try to find a psychological significance. But the reference photos of Rockwell posing show he could not have seen his own eyes; his mirror was directly opposite his studio’s massive north window, causing the reflected glare on his lenses.

As Rockwell’s assistant, Louie Lamone, recalled, paint rags and pipe ashes sometimes conspired to ignite small fires in Rockwell’s brass bucket, so the wisp of smoke in the painting rings true. Rockwell’s brass helmet, usually placed on an unused easel, crowns this one. Just as the smoke is a reminder that once Rockwell’s studio caught fire as a result of his carelessness with pipe ashes, the helmet reminds us of a favorite Rockwell story. While in Paris in 1923, Rockwell acquired it from an antiques dealer who sold it as a military relic rather than as the contemporary French fireman’s helmet Rockwell later found it to be. Alluding to its real provenance, Post editors noted for their readers when the painting was published that the helmet “could come in handy when the fire in that receptacle gets going.”

The four self-portraits on his canvas—Albrecht Durer, Rembrandt van Rijn, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent Van Gogh—are his references. They invite us to compare (as he did) how other artists tackled the problem of a self-portrait. Influenced during his student years by Durer’s superb draftsmanship, Rockwell puts him at the top of his canvas. Next in line is Rembrandt, whose painting style Rockwell admired above all others. Below it is Picasso, whom Rockwell admired greatly but whose work, he admitted, was opposite his own. Last is Van Gogh, a painter with whom Rockwell never identified, and whose style his own work never resembled. Unlike Rockwell, all four artists produced numerous formal self-portraits. Rockwell produced only two other full-color self-portraits: Norman Rockwell Painting the Soda Jerk, showing the artist from the waist up at work on his 1953 Post cover, and The Deadline, a 1938 Post cover composed much the same as this one—the rear view of the artist at work at his easel. Both are unselfconscious portraits, confirming that in 1953 and 1960 Rockwell’s view of himself continued unchanged.

In Triple Self-Portrait, Rockwell explores the idea of the artist’s identity during a time when Americans were asked to examine whether or not they could be suffering an identity crisis—a term coined by Rockwell’s own therapist, Erik Erikson, who had conceived the phenomenon as an aberration in the normal stages of development.

Multimedia

Multimedia Resources

Triple Self Portrait

Norman Rockwell

American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell Museum

- Biography article from The Norman Rockwell Museum

- Timeline of Events from the Life of Norman Rockwell

- Computer with web access, if accessible

- Index cards

- Pencils

Various books on Norman Rockwell and his work including but not limited to:

The Norman Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge by The Norman Rockwell Museum

Norman Rockwell, My Adventures as an Illustrator by Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera by Ron Schick

Norman Rockwell’s America by Christopher Finch

Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms: Images that Inspire a Nation by Stuart Murray, and James McCabe

American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell by Linds Szekely Pero

Norman Rockwell’s Counting Book by Gloria Tabor

Getting to Know the World’s Greatest Artist: Norman Rockwell by Mike Venezia

Norman Rockwell Storytelling with a Brush by Beverly Sherman

My Adventures as an Illustrator by Norman Rockwell

A Rockwell Portrait: An Intimate Biography by Donald Walton

Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms, edited by Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and James J. Kimble

Activities:

- Hand out an index card to each student.

- Ask the students to listen attentively to one another as they share personal responses throughout the lesson. Ask the students to respond by raising their hand to the following question, “Who has heard of Norman Rockwell?” In all cases, reassure them that the class will be learning about the life and work of Norman Rockwell together. First, the students will be asked to recall (silently) any prior knowledge they may have about Norman Rockwell by jotting down ideas or information they already know on one side of their index card.

- Students will be invited to share the information they have written on their index card with the class. Using these thoughts as a catalyst, a group discussion will be prompted. Student participation will be the key aspect to this discussion. You may want to encourage the students with prompts such as, “Has anyone been to The Norman Rockwell Museum?” or “Does anyone have a Rockwell print hanging in their own home?”

- Following the student driven discussion, ask half of the students to remain in their seats and distribute books on the life and work of Norman Rockwell to these students. Direct the other half of the students to the computers and give instructions on how to access the digital collection of The Norman Rockwell Museum website. Give the students the worksheet Think Sheet: Who Is Norman Rockwell 9-12. All of the students will read articles and look at images (on-line or in books) to inform themselves better about the life and work of Norman Rockwell.

- Ask the students to take notes on one image that stands out to them (students should keep track of page number or keep image up on the computer screen.) This research time will be limited to 15 minutes.

- Ask the students to return to their original table seating arrangement to gather together to analyze and share information they discovered about the life and work of Rockwell. Information may include biographical information, his schooling, his points of inspiration and the instructor will allow for judgments to be made including meaning from historical and cultural metaphors and symbols used in his work. Take this opportunity to join the conversation and point out symbols and visual clues that are connected to American culture and history.

- Project or show an image of Norman Rockwell’s Triple Self Portrait and ask the students to point out what they see in the work (not what they interpret things to be.) The class will collectively take a visual inventory. As each student contributes, restate their observation and bullet the observations on the board or an easel. You might be able to elaborate on what they have said to add more visual detail or you might ask them for clarification. You might encourage them to look more closely and carefully. After the items have been listed, point out symbols and explain some of the visual clues that are connected to American culture and history.

- Distribute a copy of the biography text and Timeline of Events from the Life of Norman Rockwell to each student. The text, which include details about Norman Rockwell’s childhood and schooling, and well as his points of inspiration, will be read together as a class. Be sure to pause for any further questions.

- Ask the students to think about themselves and what objects or symbols they would include in their own self-portrait to help show others who they are as individuals. As a student offers a suggestion, the instructor should ask how that may symbolize that individual so others better understand what a symbol is. After a few suggestions are offered, pass out a piece of drawing paper and ask the students to draw a self-portrait including at least one symbol about themselves.

- As time allows, the sketch may become the basis of a larger project (an illustration, a painting, etc.)

Assessment:

Students will be evaluated on their participation in the discussion as well as participation in analyzing the written and visual information (informal checks of understanding through questions).

Standards

This curriculum meets the standards listed below. Look for more details on these standards please visit: ELA and Math Standards, Social Studies Standards, Visual Arts Standards.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.4

- Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in the text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone, including words with multiple meanings or language that is particularly fresh, engaging, or beautiful. (Include Shakespeare as well as other authors.)

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.4

- Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in the text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the cumulative impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone (e.g., how the language evokes a sense of time and place; how it sets a formal or informal tone).

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.5

- Analyze how an author's choices concerning how to structure a text, order events within it (e.g., parallel plots), and manipulate time (e.g., pacing, flashbacks) create such effects as mystery, tension, or surprise.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.6

- Analyze a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.1

- Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.2

- Determine two or more central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to provide a complex analysis; provide an objective summary of the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.6

- Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text in which the rhetoric is particularly effective, analyzing how style and content contribute to the power, persuasiveness or beauty of the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.7

- Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.9

- Analyze seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century foundational U.S. documents of historical and literary significance (including The Declaration of Independence, the Preamble to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address) for their themes, purposes, and rhetorical features.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.1

- Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.2

- Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.7

- Analyze various accounts of a subject told in different mediums (e.g., a person's life story in both print and multimedia), determining which details are emphasized in each account.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.9-10.9

- Analyze seminal U.S. documents of historical and literary significance (e.g., Washington's Farewell Address, the Gettysburg Address, Roosevelt's Four Freedoms speech, King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail"), including how they address related themes and concepts.

- VA:Cn11.1.HSI

- Describe how knowledge of culture, traditions, and history may influence personal responses to art.

- VA:Re8.1.HSI

- Interpret an artwork or collection of works, supported by relevant and sufficient evidence found in the work and its various contexts.

- VA:Re9.1.HSI

- Establish relevant criteria in order to evaluatea work of art or collection of works.