Meet Norman Rockwell, American Illustrator

Overview:

This lesson will introduce students to Norman Rockwell, a professional artist and illustrator who had been inspired by the daily events in his everyday life in the USA. Images from books, the internet, written articles and a group discussion will be used to demonstrate how the American culture influenced Norman Rockwell in communicating his ideas as visual narratives.

This lesson is designed for one or two 30-minute class periods.

Enduring Understandings/ Essential Questions:

- Norman Rockwell is a well-known, famous American illustrator.

- Illustrators are storytellers; they are artists and create pictures to tell a story.

- Rockwell’s paintings show what American life was like from the early 1900’s to the 1970’s. His paintings progress from the portrayal of ordinary, everyday events to social inequalities.

- We can learn about Norman Rockwell by reading books, talking about and looking at artwork. We can see authentic pieces of artwork created by Rockwell at museums. We can learn more about him by visiting the digital collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

- Norman Rockwell was inspired by his surroundings (nature, politics but also ordinary events of his friends and neighbors.)

- Who is Norman Rockwell?

- What is an illustrator?

- What do you know about Norman Rockwell?

- How might you learn more about Norman Rockwell?

- What things influenced Norman Rockwell’s work?

- Grade

- 2-4

- Theme

- Four Freedoms

- Length

- This lesson is designed for one or two 30-minute class periods.

- Discipline

- National Visual Arts Core Standards

- Vocabulary

- Art Director; Biography; Canvas; Civil Rights; Community; Culture; Editor; Exhibit; Freelance; Gallery; Illustrate/ Illustrator; Model/Pose; Ordinary; Patriotic; Poverty; Series; Self-Portrait; Symbol

Objectives:

- Students will share any prior knowledge regarding Norman Rockwell that they may have.

- Students will discuss the information presented in a biography article and book.

- Students will be exposed to The Norman Rockwell Museum Digital Collection: collections.nrm.org.

- Using prior knowledge, the information from the articles and The Norman Rockwell Museum Digital Collection, the students will make judgments on Rockwell’s work including meaning from historical and cultural metaphors and symbols.

- Students will listen attentively to one another as they share personal responses about the specific artworks.

Background:

Norman Rockwell was born in New York City in 1894. He was a super-skinny kid and was terrible at sports, but he always knew that he wanted to be an artist. His paintings would tell a story without words. His work was influenced by family, friends, neighbors and vacations. He worked for more than sixty years painting scenes of people in their everyday life.

Rockwell was a teenager when he was hired to work as the art director of Boys’ Life, the official magazine of the Boy Scouts of America. In this job, Rockwell had to make all of the decisions in how the magazine should look. When he was 22 years old Rockwell painted his first cover for a popular American magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, and continued to paint 323 covers over the next 47 years.

In 1916, the same year that his first cover was on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell married Irene O’Connor. Their marriage lasted 14 years, then they divorced. In 1930 he married a teacher, Mary Barstow. Norman and Mary Rockwell had three sons, Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter. Nine years after they were married, the family moved to a small town in Vermont. The community of people in Arlington were supportive of Norman Rockwell and his work. Their neighbors and friends were often eager to be models for his work.

In 1943, President Franklin Roosevelt’s spoke to the American people in a speech called “The Four Freedoms.” Norman Rockwell felt the President’s message was important and wanted to illustrate it. The Four Freedoms paintings were Norman Rockwell’s interpretations of the Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. These four paintings became tremendously popular.

The Rockwell family moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts in 1953. Sadly, six years later his wife, Mary, died unexpectedly. Shortly after, Rockwell met a retired teacher, Molly Punderson, at the library and they became close friends and eventually married. It was at this time that Rockwell began to paint pictures illustrating some of his most worrisome concerns and deepest interests, including civil rights, poverty, and the exploration of space.

In 1977 the President presented Rockwell with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom! Rockwell became one of America’s all-time favorite artists before he died in 1978.

Materials:

Multimedia Resources

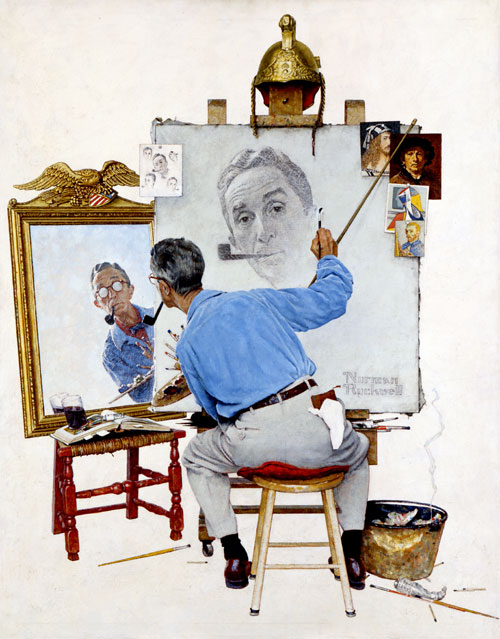

Triple Self Portrait

Norman Rockwell

American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell Museum

Classroom Supplies:

- Getting to Know the World’s Greatest Artist: Norman Rockwell by Mike Venezia

- Biography article from The Norman Rockwell Museum

- Timeline of Events from the Life of Norman Rockwell

- Computer with web access and projector

- Easel or board for writing the visual inventory

- Drawing Paper

- Pencils

Additional Teaching Resources:

The Norman Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge by The Norman Rockwell Museum

Norman Rockwell, My Adventures as an Illustrator by Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera by Ron Schick

Norman Rockwell’s America by Christopher Finch

Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms: Images that Inspire a Nation by Stuart Murray and James McCabe

American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell by Linds Szekely Pero

Norman Rockwell’s Counting Book by Gloria Tabor

Norman Rockwell: Storytelling with a Brush by Beverly Sherman

My Adventures as an Illustrator by Norman Rockwell

A Rockwell Portrait: An Intimate Biography by Donald Walton

Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms, edited by Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and James J. Kimble

Activities:

- Ask the students to listen attentively to one another as they share personal responses throughout the lesson.

- Ask the students, “Who has heard of Norman Rockwell?” Student participation will be the key aspect to this discussion. However you may want to encourage the students with prompts such as, “Has anyone been to The Norman Rockwell Museum?” or “Does anyone have a Rockwell print hanging in their own home?”

- Read Getting to Know the World’s Greatest Artists: Norman Rockwell by Mike Venezia to the students, pausing to reinforce information and allowing for questions to be asked when something is unclear.

- Access the digital collection of The Norman Rockwell Museum website collection at: collections.nrm.org and project the site on a screen for all students to see. Display Rockwell’s Triple Self Portrait and ask the students to point out what they see in the work (not what they interpret things to be.) The class will collectively take a visual inventory. As each student contributes, restate their observation and bullet the observations on the board or an easel. You might be able to elaborate on what they have said to add more visual detail or you might ask them for clarification. You might encourage them to look more closely and carefully.

After the items have been listed, point out symbols and explain some of the visual clues that are connected to American culture and history. Continue to browse through the online collection for no longer than 10 minutes, according to the direction of the students, taking time to note some of the cultural symbols Rockwell used in his work.

- Distribute a copy of the biography text and Timeline of Events from the Life of Norman Rockwell to each student. The text, which include details about Norman Rockwell’s childhood and schooling, and well as his points of inspiration, will be read together as a class. Be sure to pause for any further questions.

6. Ask the students to think about themselves and what objects or symbols they would include in their own self-portrait to help show others who they are as individuals. As a student offers a suggestion, the instructor should ask how that may symbolize that individual so others better understand what a symbol is. After a few suggestions are offered, pass out a piece of drawing paper and ask the students to draw a self-portrait including at least one symbol about themselves.

Assessment:

- Students will be evaluated on their participation in the discussion.

- Students will be evaluated on their participation in analyzing the written and visual information.

- Students will be evaluated through informal checks of understanding.

Standards

This curriculum meets the standards listed below. Look for more details on these standards please visit: ELA and Math Standards, Social Studies Standards, Visual Arts Standards.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.2

- Recount stories, including fables and folktales from diverse cultures, and determine their central message, lesson, or moral.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.4

- Describe how words and phrases (e.g., regular beats, alliteration, rhymes, repeated lines) supply rhythm and meaning in a story, poem, or song.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.5

- Describe the overall structure of a story, including describing how the beginning introduces the story and the ending concludes the action.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.6

- Acknowledge differences in the points of view of characters, including by speaking in a different voice for each character when reading dialogue aloud.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.3.2

- Recount stories, including fables, folktales, and myths from diverse cultures; determine the central message, lesson, or moral and explain how it is conveyed through key details in the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.3.4

- Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, distinguishing literal from nonliteral language.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.3.5

- Refer to parts of stories, dramas, and poems when writing or speaking about a text, using terms such as chapter, scene, and stanza; describe how each successive part builds on earlier sections.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.3.6

- Distinguish their own point of view from that of the narrator or those of the characters.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.4.2

- Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text; summarize the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.4.5

- Explain major differences between poems, drama, and prose, and refer to the structural elements of poems (e.g., verse, rhythm, meter) and drama (e.g., casts of characters, settings, descriptions, dialogue, stage directions) when writing or speaking about a text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.4.6

- Compare and contrast the point of view from which different stories are narrated, including the difference between first- and third-person narrations.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.2.1

- Ask and answer such questions as who, what, where, when, why, and how to demonstrate understanding of key details in a text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.2.7

- Explain how specific images (e.g., a diagram showing how a machine works) contribute to and clarify a text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.2.9

- Compare and contrast the most important points presented by two texts on the same topic.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.1

- Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.7

- Use information gained from illustrations (e.g., maps, photographs) and the words in a text to demonstrate understanding of the text (e.g., where, when, why, and how key events occur).

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.9

- Compare and contrast the most important points and key details presented in two texts on the same topic.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.1

- Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.7

- Interpret information presented visually, orally, or quantitatively (e.g., in charts, graphs, diagrams, time lines, animations, or interactive elements on Web pages) and explain how the information contributes to an understanding of the text in which it appears.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.9

- Integrate information from two texts on the same topic in order to write or speak about the subject knowledgeably.

- VA:Cn11.1.2

- Compare and contrast cultural uses of artwork from different times and places.

- VA:Cn11.1.3

- Recognize that responses to art change depending on knowledge of the time and place in which it was made.

- VA:Cn11.1.4

- Through observation, infer information about time, place and culture in which a work of art was created.

- VA:Re8.1.2

- Interpret art by identifying the mood suggested by a work of art and describing relevant subject matter and characteristics of form.

- VA:Re8.1.3

- Interpret art by analyzing use of media to create subject matter, characteristics of form, and mood.

- VA:Re8.1.4

- Interpret art by referring to contextual information and analyzing relevant subject matter, characteristics of form, and use of media.

- VA:Re9.1.2

- Use learned art vocabulary to express preferences avout artwork.

- VA:Re9.1.3

- Evaluate an artwork based on given criteria.

- VA:Re9.1.4

- Apply one set of criteria to evaluate more than one work of art.